Evolution is one of those topics I really enjoy learning and teaching, particularly with open activities. The War of the Evolutionists Web Scavenger Hunt and Mock Trial, and the Evolution and Adaptation games are just some of my attempts to engage students in ecology and evolution.

Of these The Evolution Game, created by Simon Boswell and Phil Lewis, comes the closest to emulating the process and product of evolution. The rules and gates of the game are the processes of ecology and evolution; it is not a trivia game, a passive one, nor one like charades whose play has little semblance to evolution. As such The Evolution Game exemplifies that rare and powerful quality game that embeds students in their learning by forcing them to deal with and adapt to the “rules” or processes of evolution and ecology. It is however a long-term activity, like Risk, of both strategy and chance.

The Evolution Game © 1997 Simon Boswell | more info (via: stefras)

The Evolution Game © 1997 Simon Boswell | more info (via: stefras)Published with permission

Just yesterday, I came across another great activity that comes close to emulating both ecology and evolution. The activity, created by Tyler Rhodes and featured by Scientific American, consists of two parts: a student-centered exercise and a technical exercise. The student exercise takes about an hour, or one period, to conduct. The technical one — creating a video — took Tyler, who claims to be expert enough to work efficiently, three months to complete. So feedback in the form of product is delayed, though formative feedback is immediate and embedded in the students’ own activity.

The idea is simple, if not elegant, and follows the same design premise as The Evolution Game and Bernie Dodge’s formula for game design that “Elegance = congruity between the forms of the game and structures within the content“.

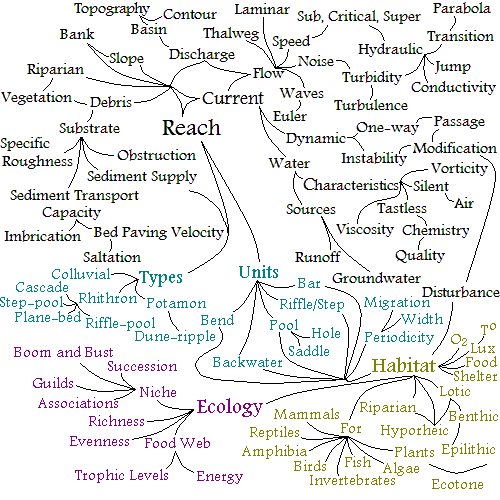

Tyler drew a nondescript salamander-like creature and enlisted five independent groups of students (from five schools) to draw copies of this creature.

Once the students compared and discussed the new creatures, Tyler “exposed” the creatures to some ecological stress or change. The students had to vote which creatures perished based on the new ecology and the features of the creatures. According to Tyler, ninety-eight percent of the creatures perished (in a class of 30, where each student drew one creature, one creature survived). Tyler gathered the extinct creatures and repeated the exercise five more times with the survivors, each time with a new ecological event wiping out ninety-eight percent of the creatures. The six generations were kept or labelled apart.

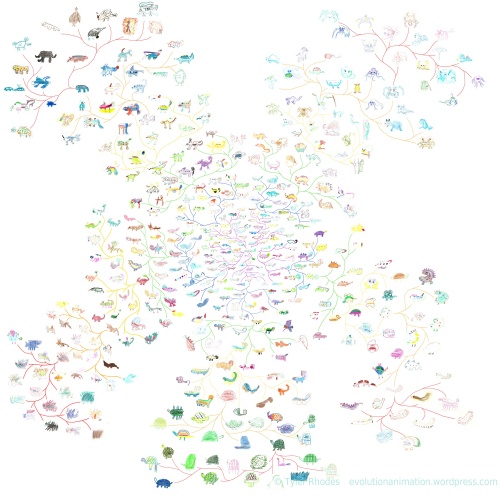

The exercise illustrated branching phylogenetic evolution and coevolution — rather than the defunct linear evolution — as shown in the following drawing, where each “arm” of creatures came from a separate class of students, so giving five arms.

A Wheel of Life © 2012 Tyler Rhodes | more info (via: Tyler Rhodes)

A Wheel of Life © 2012 Tyler Rhodes | more info (via: Tyler Rhodes)Click on the image to enlarge it.

What is nice about this exercise is that the students actively engage in, and embed themselves in, the process of natural selection by ecological change. They, being the active agents in both the creation and voting off of these creatures, were given the opportunity to experience and learn about the fundamental processes of evolution, much like The Evolution Game.

Tyler designed this process after a “Chinese Whisper” or “Telephone” game, where a message is passed from person to person and changes through mutation as it is delivered. In fact he presented it as a game. The message, however, was visual — the drawing of the creature — and the changing ecology affected the message. Tyler was specifically looking for a way to branch the creature evolution like a phylogenetic tree and his use of the “Chinese Whisper” or “Rumour” game enabled this.

Here is the final video.

The creatures in this video are those from the top-left arm of the Wheel of Life tree illustrated above. Tyler promises four more videos, for each of the remaining four groups of students. And he invites teachers to take his initial nondescript salamander-like creature, repeat his method and e-mail him facsimiles of the creatures created. If teachers take him up on the offer, he can bank, analyze and share some really interesting evolutionary results from the project. His conclusions should be interesting.

For more information on Tyler’s project, visit his blog, Evolution!, documenting his progress.

How can we emulate Tyler’s project for outcomes in our classrooms? Or have you done so already?

Follow @stefras